Minneapolis Is Not Even a Close Call – a Lawsplainer on Officer-Involved Shootings

AP Photo/Tom Baker

Posted for: Rotorblade

ICE Officer’s Use of Deadly Force Deemed Justified Under Federal Law and Supreme Court Precedent

An ICE officer’s decision to use deadly force during a vehicle encounter in Minneapolis was legally justified under long-standing federal law and Supreme Court precedent, based on what a reasonable officer would have perceived at the moment the force was used.

The critical legal inquiry is not the driver’s intent after the fact, nor speculation based on hindsight, but the perspective of the officer confronting an immediate and rapidly evolving threat. Under the Fourth Amendment, all uses of force by law enforcement—deadly or non-deadly—are considered “seizures” and must be objectively reasonable in light of the totality of the circumstances known to the officer at the time.

Authority of ICE Officers

ICE employs two categories of law enforcement personnel: Special Agents and deportation officers. ICE Special Agents are federal criminal investigators under the GS-1811 series and are fully authorized to carry firearms, conduct investigations, and make arrests for federal crimes, including violations under Title 8 (Aliens and Nationality) and Title 18 of the U.S. Code.

Contrary to claims circulating on social media, ICE officers do have legal authority to briefly detain U.S. citizens during lawful investigations and to arrest citizens who obstruct, interfere with, or assault federal officers engaged in official duties.

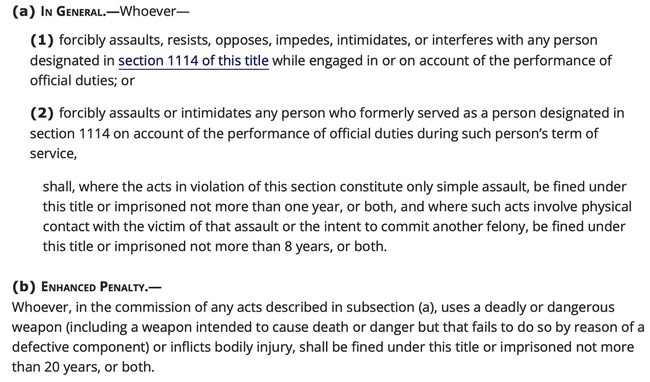

Title 18 U.S.C. § 111 makes it a federal crime to assault, resist, oppose, impede, intimidate, or interfere with a federal officer performing official duties. The statute does not require physical contact. An assault is complete if the officer is placed in reasonable fear of immediate bodily harm.

Vehicles as Deadly Weapons

Federal courts—including the Eighth Circuit, which covers Minnesota—have consistently held that a vehicle may qualify as a deadly or dangerous weapon when used in a manner capable of causing serious bodily injury or death. Actual impact is not required.

In United States v. Wallace (2017), the Eighth Circuit upheld a conviction under § 111(b) where a driver used her vehicle in a way that forced a federal officer to jump onto the hood to avoid being struck. The court emphasized that a vehicle used to threaten an officer is no longer mere transportation—it becomes a weapon.

The Encounter in Minneapolis

In the Minneapolis incident, the ICE officer was lawfully attempting to detain the driver after she had obstructed operations and failed to comply with repeated commands to stop and exit her vehicle. The officer observed the vehicle reposition and accelerate in his direction after he had clearly identified himself and issued commands.

At that moment, a reasonable officer could conclude that the driver had committed an aggravated assault with a deadly weapon and posed an imminent threat—not only to the officer himself, but also to others in the immediate area and along the vehicle’s intended path of travel.

Whether the vehicle ultimately struck the officer is legally irrelevant. Under federal law and jury instructions adopted by the Eighth Circuit, the assault is complete once the officer is placed in reasonable fear for his life or safety.

Supreme Court Guidance on Deadly Force

Supreme Court decisions over the past four decades establish that deadly force is constitutionally reasonable when an officer has probable cause to believe a suspect poses a serious threat of physical harm to the officer or others.

In Tennessee v. Garner (1985), the Court held that deadly force may be used to prevent escape when a suspect poses such a threat. In Graham v. Connor (1989), the Court clarified that use-of-force decisions must be judged from the perspective of a reasonable officer on the scene, not with hindsight, and must allow for split-second judgments in tense and rapidly evolving circumstances.

Later cases such as Scott v. Harris (2005) and Plumhoff v. Rickard (2014) further confirmed that officers may use deadly force to end a dangerous vehicle flight that threatens public safety—even if the vehicle is only beginning to move or the officer is no longer directly in front of it.

The Court has also rejected the notion that each individual shot must be independently justified once deadly force is lawfully initiated. Officers are not required to stop firing until the threat has ended.

These are the only images I needed to see to form my opinion.

One ICE Officer is approaching her car and giving her lawful commands through her open driver’s side window. The car is in “Reverse” and her wheels are cut to the left. There is no ICE Officer to her front.

Here she has moved approximately 3 feet back as you can see from the relationship of her tires to the white line in both images. The ICE Officer to her front is still visible. In this image her “Reverse” white tail lights are off — she has shifted into drive. Her front tires are still cut to the left, and her front end has reoriented more towards the Officer now in the center of her front end.

This is as far backwards as she travels. Her brake lights are now off — she’s in “Drive” and her foot is no longer on the brake. The ICE Officer is now in front of her driver’s side headlight, and her wheels are facing straight ahead. At this moment her front wheels break traction as she attempts to accelerate forward. Had the tires not spun on the ice she would have made immediate and forceful contact.

Totality of the Circumstances

In evaluating the officer’s actions, the totality of circumstances includes the driver’s prior conduct: blocking traffic, refusing lawful commands, positioning the vehicle toward the officer, and accelerating in a manner that created a reasonable fear of death or serious injury.

The Constitution does not require officers to step aside, allow a suspect to flee, or gamble with public safety in the hope that no one will be harmed. When faced with a suspect who has already demonstrated willingness to use a vehicle as a weapon, an officer is not required to take that risk.

Conclusion

Based on federal statutes, binding Supreme Court precedent, and Eighth Circuit case law, the ICE officer’s decision to use deadly force was objectively reasonable under the Fourth Amendment. The law does not turn on the driver’s claimed intentions or post-incident speculation, but on what a reasonable officer would have perceived at the moment force was used.

From that perspective, the officer acted within the bounds of constitutional authority to stop an imminent and serious threat to himself and to the public.